The teachings that came from early Mesopotamia and developed throughout the middle ages and Renaissance period, and which emerged from the period of enlightenment had become weighed down with fanciful ideas and delusions. Unfortunately, the astrology of today still predominates these fanciful delusions and although astrology remains popular in 21st century culture, it also remains much maligned and is often not taken seriously, seen as only valuable for entertainment purposes.

The original basis for astrology most likely began as the study of relationships between the cosmos and terrestrial life in the form of astro-meteorology. Humans came to understand the cycle of seasons and the effect they had on the environment. Over time, this developed into a world view that was formed with a mixture of observation, philosophy and religion.

The Beginning of Scientific Thinking

The work of Galileo (1564 – 1642) began to establish experimentation as a cornerstone of modern science. Using a telescope, he found that the theory put forward by Copernicus (1473 – 1543) that the Earth rotates on its own axis once a day, and revolves annually around the Sun was correct. This put him in conflict with the Catholic Church who attempted to force him to recant his views. He spent the rest of his life under house arrest.

It heralded what became known as the Scientific Revolution. At this time astronomy and astrology parted ways. Astronomy, or the study of the physical elements of the cosmos became the predominant field of scientific endeavour, and astrology was banished by both science and religion.

By this time, astrology had become a thickly spun web of irrelevant teachings with the concept of applying the “as above, so below” principle to every possible kind of manifestation or situation. This often meant forcing the “above” to accord with a world view of the “below”, attempting to see a greater whole in every smallest detail of life.

There was a revival in the practice of this kind of astrology around the early part of the 20th century. However, at the same time a group of astrologers formed the view that a new scientific form of astrology should be established. This could not happen though if advocates were unwilling to examine and discriminate between all the various components that made up the layers forming the delusions and superstitions that remained in the system that had been handed down over the millennia.

A new type of astrology began to emerge in Germany at this time. Like its traditional counterpart, it sought to investigate the relationships between the heavenly bodies and the effect they have on the lives of humans, however the concepts and methodologies of cosmobiology were quite different. Traditional astrology did, and still does to large degree seek to understand the individual and their destiny in their entirety, almost as a God-like world-view. Cosmobiology opposes such an all embracing perspective. The term Kosmobiologie (Cosmobiology) was coined by early proponents of this new science to differentiate it from the popular astrology of the day.

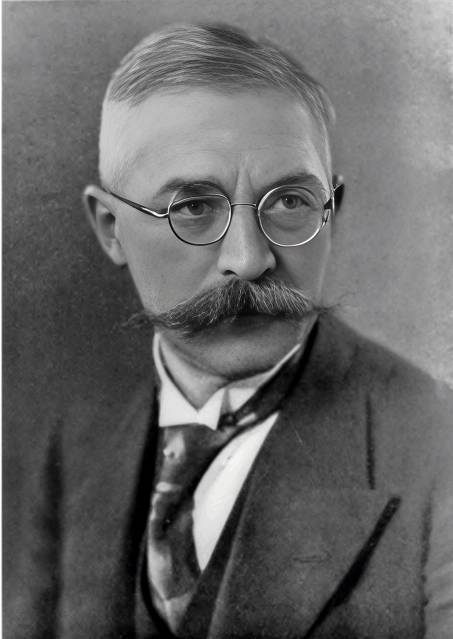

The year 1928 heralded what probably marks the beginning of this new form of astrology with the publication by Dr. H. A. Strauss of “Jahrbuch für Kosmobiologische Forschung” (Cosmobiological Research Yearbook). Unfortunately, only two issues of this publication were ever published.

One of the most influential groups at the time was the Hamburg School, led by Alfred Witte (1878 – 1941). Witte revived a concept of midpoints which he named planetary pictures, which was similar to Arabic parts which developed historically in the Arab world. He further hypothesised existence of several Trans-Neptunian objects besides Pluto and calculated ephemerides for them. His work was rejected in his later years, and he was also considered an enemy of the Third Reich, with his work being banned and destroyed. Although not interned, Witte was heavily monitored by the Gestapo and he died by suicide in 1941.

However, it was Reinhold Ebertin (1901–1988), a key figure in cosmobiology’s development, who would cement the field’s place in both astrology and medicine. Ebertin believed that astrology had a direct influence on health, but he took it a step further by applying astrological techniques in a scientifically rigorous manner. A former student of Witte, Ebertin is often credited with formalising cosmobiology, integrating it with medical practice and emphasizing empirical methods. Ebertin published his seminal work, The Combination of Stellar Influences (1953), which presented a detailed system for understanding the relationships between astrological factors—particularly planetary positions—and physical and psychological health.

Ebertin refined the concept of midpoints he had learned from Witte, and rejected the hypothetical planets Witte had proposed, while greatly expanding on the work of Witte. He emphasised the use of astrological charts alongside biological data, creating a system that combined traditional astrological analysis with the study of health patterns. His empirical approach was groundbreaking, as it moved away from purely theoretical astrology and incorporated data-driven analysis to examine the links between celestial bodies and health outcomes.

The Interwar Period: The Influence of Dr. Landscheidt and Friedrich Feerhow

The interwar period, particularly the 1920s and 1930s, saw the rise of several key figures in cosmobiology who helped formalize and expand the field. Dr. Theodor Landscheidt (1926–2004) and Friedrich Feerhow (1893–1964) were pivotal in shaping the direction of cosmobiology, with contributions that expanded its scope from individual health to a more comprehensive understanding of biological rhythms and solar influences.

Dr. Landscheidt, a physicist and astrologer, is considered one of the foremost figures in the development of cosmobiology. His research focused on the cyclical relationship between planetary movements, solar activity, and human health. Dr. Landscheidt proposed that solar cycles, particularly the sunspot cycle, had a direct effect on biological rhythms on Earth. His studies suggested that the Sun’s activity could influence not only the weather and environment but also the biological systems of living organisms. By correlating solar and planetary cycles with health data, Landscheidt provided a broader framework for cosmobiology, one that encompassed both solar influences and the planetary configurations studied by Ebertin and the Hamburg School.

In contrast to traditional astrology, Dr. Landscheidt emphasized the need for statistical analysis and empirical validation. He advocated for the use of scientific methods to examine astrological phenomena, seeking to provide objective evidence for the astrological claims that had long been made about human health and behaviour. His contributions to cosmobiology were crucial in making the field more scientifically acceptable, pushing the boundaries of astrological research into more measurable and verifiable domains.

Friedrich Feerhow (1893 – 1964), a physician and astrologer, made significant contributions to the medical side of cosmobiology. Feerhow was one of the early figures to apply astrological principles to the understanding of diseases, medical conditions, and psychological disorders. He worked closely with other astrologers like statistician Karl Krafft (1900 – 1945), and Ebertin to identify correlations between planetary configurations and specific health conditions, emphasising the importance of planetary aspects in understanding health issues. Feerhow’s medical astrology helped establish a deeper connection between astrology and the biological sciences, making cosmobiology more relevant to the field of healthcare.

The War Years: Challenges and Adaptation

The outbreak of World War II had a profound impact on the development of cosmobiology in Germany. The rise of the Nazi regime and its focus on controlling intellectual and scientific discourse posed significant challenges to astrologers, many of whom were either forced into exile or silenced by the regime. Although astrology was not explicitly banned, it was heavily marginalized by the government due to its association with occult and esoteric traditions.

The war years provided a period of intense hardship for many cosmobiologists. Karl Krafft, for example, faced persecution and ultimately died during the war. Despite this, cosmobiologists continued to study in private, albeit under increasingly difficult circumstances. The ideological constraints of the time forced many to take a more discrete approach, often conducting research in isolation or exile.

However, these years also had a significant impact on the development of cosmobiology. As the war forced astrologers and cosmobiologists into seclusion, many took the opportunity to refine their methods and deepen their understanding of the connections between celestial movements and biological processes. The dislocation caused by the war led to a period of reflection and development for cosmobiologists like Dr. Landscheidt and others who continued to explore new ideas about the influence of solar activity on human health.

Post-war, there was a resurgence of interest in astrology and cosmobiology. The rebuilding of Germany and the eventual relaxation of ideological constraints allowed for the return of cosmobiological research. Figures like Ebertin continued to expand the field, with new methods of empirical study that reflected the lessons learned from the war years.

The Post-War Period: The Aalen School and the Expansion of Cosmobiology

Following World War II, the Aalen School emerged as a key intellectual hub for the development of cosmobiology in Germany. The Aalen School sought to integrate cosmobiological principles with modern medical and biological knowledge. The school emphasised empirical research, statistical analysis, and the use of rigorous methods to correlate planetary positions with health outcomes.

The Aalen School was particularly influential in bridging the gap between traditional astrology and modern scientific approaches. By incorporating methods from medicine, biology, and statistics, the Aalen School helped establish cosmobiology as a field that could be approached with scientific rigour while maintaining its roots in traditional astrology. Researchers from the Aalen School developed systematic methods for correlating planetary aspects with diseases and illnesses, contributing to the growing body of evidence that supported the link between astrology and health.

Ebertin’s influence remained strong during this period, as his work continued to be a foundational reference for cosmobiologists. His methods, which combined astrology with biological data, were adopted by the Aalen School and other researchers seeking to explore the relationship between celestial bodies and human health. The success of cosmobiology in the post-war era reflected the growing acceptance of astrology as a field worthy of empirical investigation.

Late 20th and Early 21st Century

Cosmobiology started to make its way into the English speaking world with the translation of the works of Reinhold Ebertin and their publication in the 1970s. Although there was some interest in this science, Western astrologers tended to combine what cosmobiology teaches with the outdated superstitions still found in astrology, thus diluting its scientific rigour.

A few key figures emerged such as Eleonora Kimmell (1923 – 2023) and Aren Ober (1933 – 2020) in the USA, and Doris Greaves (1919 – 2007) in Australia, along with Dr Baldur Ebertin (1933 – 2020), Reinhold’s son, who all taught and wrote books about cosmobiology. Aside from that only a few locally known personalities around the world who tended to work more with groups of astrologers than to collaborate with scientists have kept the practice alive.

References

- Ebertin, R. (1972), Applied Cosmobiology, Ebertin-Verlag, ISBN: 0-86690-086-1

- Ebertin, R. (1972), The Combination of Stellar Influences, Ebertin-Verlag, ISBN: 0-86690-087-X

- Kimmell, E. (2000), Cosmobiology for the 21st Century, American Federation of Astrologers, ISBN: 0-86690-504-9

- Landscheidt, T. (1989), Sun-Earth-Man: A Mesh of Cosmic Oscillations, Urania Trust, ISBN: 1-871989-00-0